- Job Lot : Photographs From the Ambassador Years

The Ambassador - The British Exports Magazine was founded, edited and published by Hans and Elsbeth Juda. It appeared monthly in 4 languages (English, Portuguese, French and German), could prove a circulation of 23 000 copies and was distributed in 90 countries. The magazine was run by Hans and Elsbeth Juda from its inception in 1940 to 1965. In 1961 it was sold to Thomson Publications who continued publishing until 1972. The most complete sets are held in the archives of the V& A and at the British Library, London.

Uscha Pohl: How did The Ambassador come about?

Elsbeth Juda: When we came to England we thought how underexposed industry and industrial design was. Opening a London office for the Dutch Trade magazine International Textiles was one way to change this. Their main office was in Amsterdam and it was arranged that if the Germans invaded Holland the magazine would be published from London. In 1940, they didn’t have much choice but to go with their occupiers, so we started our own; with no capital at all and little money, we all had to work very hard.For a tradepaper it was most unusual to separate editorial from advertising (the designer clearly separated the two), as was to have a certified circulation which meant you could charge for publicity. We had advertising salesmen but we all felt responsible for the whole content. We decided that textiles were rather limiting so we added one month a motorcar supplement, then bicycles or industrial design; 12 issues a year.

The only time we ever had an enquiry from the IRS, they called up ‘You have a man called Mr Bowden, who earns more than you do, the boss. How do you explain that?’ Thinking… you know,… And I said ‘Thank goodness he earns more than I do because without the advertising sales there would be no magazine.’

UP: How did you manage to keep publishing throughout the war?

EJ: The government was keen on exports (Hans came up with the theme ‘Export or Die’). We were supplied with paper through Portugal, Britain’s oldest ally, and we were made to publish. My husband also worked for the Ministry of Information while I worked separately as photographer. One of my first war jobs was to take photographs of airmen’s ‘shot-off bottoms’, and then documenting flying glass wounds for text books.UP: You both were from Germany but represented Britain and Britishness to the world.

EJ: It was quite an extraordinary thing, here was this (German) couple making the British Export Magazine. But Hans felt that this was needed, and of course he understood exports better by being a foreigner. You personally as well as the magazine were a link to the world.

All our American contacts really came from people who wanted to find out what this strange magazine was that came out of England. And so Stanley Marcus, (whose grandfather actually started Neiman Marcus but he was the one who made it what it became) was sent to London by Roosevelt to find out what was going on. When he asked his (American) friend Gordon Yates, then chairman of Elizabeth Arden Europe, to find him ‘this strange fellow called Hans Juda who makes this interesting magazine that came all through the war’ he was told ‘That’s not very difficult, we are playing bridge with him tonight.’ It became a very serious and great friendship.

- UP: Fashion and photography were not exactly obvious careers for you.

EJ: I didn’t have a clue about fashion. I am the daughter of a German philosophy professor who wanted me to go to Oxford, to become, probably, a librarian; because that’s all we had, books. He had me exempted from drawing, painting or anything visual at school. ‘She is very good at languages but she has no talent for visual things. So, exempt her,’ is how he put it to the school. Which was probably something that made me keener. I did Spanish and all kinds of things while other people did drawing and painting. I therefore came to art very late in life and with a huge woosh because when it is kept from you want it all the more.

We had nothing but books at home, we had 20 000 books - no money but 20 000 books! I don’t think there was even a photograph up in our house. In fact if you go to the Freud house here in Hampstead, his workroom with the couch was very much like my father and mother’s rooms, with the sliding doors between them.And actually: Freud saved my life when I was a baby. One day Freud came to do something about extra-sensory perception with my father. When he walked in, my father asked ‘Freud, as you are also a doctor of medicine, can you look at my second child? She keeps screaming! We put her as far away as we can on the furthest terrace but we cannot stop her, she keeps crying.’

And Freud went to find this poor child on the terrace at the end of the apartment. Coming out he said ‘She is black and blue, what do you feed her on?’ ‘Oh, her mother’s milk,… my son has been on the same milk and is 2 years old, why shouldn’t she thrive? ‘I think she looks starved. I suggest you get he a wet nurse today and put her in the sun from 20 seconds to half an hour.’ I survived and now I am 98 years old tomorrow, which is ghastly. UP: How did you become a photographer?

EJ: I didn’t start as photographer. Our first art director at The Ambassador was Moholy Nagy, from the Bauhaus and I had to assist him as we couldn’t afford an assistant. He said ‘Elsbeth you have a very good eye. My first wife, Lucia, who taught us all at the Bauhaus, will come and teach you.’ Which she did and we took photographs together... Living in a one room flat, the developing room was the kitchen and the fixing was the bathroom. One day I thought ‘my poor husband doesn’t know if he’s eating soup or developer!’So I went round with these little pure Bauhaus photographs, saying I’d like ‘any’ job… The reply was always the same: ‘A woman..., what’s the 'Bowow'...?,’ ‘It’s 'Bauhaus', fundamental design,…’ ‘Never heard of it, a woman, married,…’ And then one day someone offered me a darkroom boy job.

I was a darkroom boy for 2 years. Then the so-called operator wasn’t back from his holidays when there was a Revillon fur catalogue to do. 24 insured furcoats, the models, the clients, everything and everyone was there, just no photographer! He was in the South of France and just hadn’t bothered to inform anybody that he wasn’t back.

So they said ‘Jay, take your overall off… and stand behind the camera’; which I did and because I had brought the slides in and out and had also looked from the darkroom door I understood how the camera worked. So I photographed the fur coats which was hell because every hair had to show and it was of course the hottest summer and there was a pneumatic drill in the street. But we got it done.

When it was finished I was called into the outer office which was where these reps sat who sold photographs and Tommy Thompson, the lazy owner of the studio, and there was a box of gold watches from Fortnum’s. They said ‘This is to thank you.’ I said ‘This is nice’... ‘No no, this is your welcome’ and so I was out of the darkroom and became the operator.

UP: Why ‘Jay’ rather than Elsbeth Juda?

EB: I became ‘Jay’ when they hired me as a darkroom boy. They asked ‘What can we call you?’ ‘My name is Juda!’ They said ‘Oh that’s a long way,’… ‘Well, Jay is my initial’ and that’s how. ‘Jay, where the hell are the slides, Jay, find that, Jay, where are the contacts, Jay…’ Jay is very nice and short. As a photographer to have a short name is very good.UP: You photographed Sir Winston Churchill while he was sitting for his portrait by Graham Sutherland. The portrait upset Churchill so much when he eventually saw it that his wife sadly and famously made it disappear. Your records of Churchill posing as in the painting itself, are the only ones remaining.

EB: The Churchill portraits were a very very privileged occasion because Sutherland was a friend and he called up ‘help help, I can’t finish the portrait’ - which was overdue.

He had to have certain details and asked me to bring my camera, do it as un-showily as I could and give him some prints. He had to finish because it was a present from both houses for Churchill’s 80th birthday.

When it was unveiled Churchill was so cross because he had thought he would be in his Garter Robes and there he was in his zoot suit. And, his feet were cut off! He walked out. Sutherland rang us up in despair, and we said ‘Send it to us, we’ll look after it, easily,’ because we lived back to back with Churchill. Then Churchill learned he had to have the painting as it was a present from both Houses of Parliament and we had to send it back over. Churchill’s wife later said that she had destroyed it because it upset him so much.

UP: Is there any particular highlights for you personally amongst the photographs in the exhibition?

EB: I like the photos of the craftsmen very much because they no longer exist. I am not proud of anything, ever. But I think it is a very good thing to have caught them while they were still about. Like this picture of these two workmen who have come back to Wedgwood standing there in their Sunday blacks and their white knitted scarves, discussing their careers and retirement. It doesn’t happen anymore. The others, I think it everything still happens. They were all jobs.That’s why I wanted to call the exhibition ‘job lot’. Art is not involved. They were jobs, and the best I could do. The best you can do in a time allotted, is a job lot. I had to go and face the same editorial problem: there was an Irish Linen feature once a year, Lancashire, twice, Yorkshire and Scotland ditto. To photograph fabrics you go either to Glenurquhart and drape it over a fence or you go to Government House to do Irish linen in ‘What the Butler Saw’, photograph a chambermaid with a tray…

It’s not always either that easy or the idea doesn’t come immediately and so you have to think up something that is different. That’s how I started traveling with models. As we were trying to sell to the world I thought ‘let’s take the stuff to the world’.

I was one of the earlier photographers going to Australia, Brazil, etc. Now everybody goes everywhere because we are so travel-merry. The challenge was to find a different way 4 times a year - there wasn’t a great deal of change in the collections you had to photograph.

[EB] If you can find pleasure and fun you become inventive. For a cotton issue for example I took Barbara Goalen [the super model of the time] to the CPA, the Calico Printers Association. Instead of having 18 fabrics lying there and photographing them, I said, ‘well, let’s try something’. Barbara Goalen was great; to all these stupid directors she said ‘If you will follow me around I want you to carry a full length mirror for me’.

The first time I interviewed the chairman of the merchant tailors guild I had never heard of a ‘turn up’ or ‘lapel’, or ‘inside leg measurements’. Exactly like the Paris couture later on where we would sit in the Ritz bar in Paris and discuss whether the hemline comes to below the knee, just on, or 1/2 an inch above. Major, major things of interest. And of course the Paris couture existed to be the lead momentum of all fashion.

Now fortunately it is how you put yourself together because fashion doesn’t exist anymore. And isn’t it a wonderful thing!

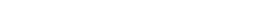

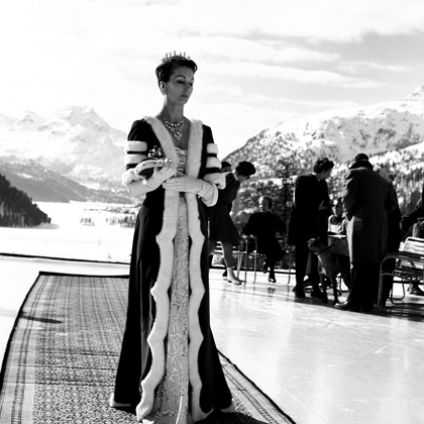

Coronation on Ice: Barbara Goalen makes her exit, St Moritz, 1953 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Barbara Goalen, Milling Around Lancashire, 1952 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Winston Churchill, Chartwell, Kent, 17 October 1954 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Winston Churchill, Chartwell, Kent, 17 October 1954 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Winston Churchill, Chartwell, Kent, 17 October 1954 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Rory and Alexander McEwen, Scotland, 1950 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Margot Fonteyn double exposure, hat fitting with Rose Vernier, 1949 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Critic Kenneth Tynan with his daughter, Tracey, Bayswater, 1953 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Antony Armstrong-Jones in his studio, 1952 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Henry Moore in his studio at Much Hadham, Hertfordshire, working on King and Queen, 195 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Pop artist Peter Blake with model Marie-Lise Gres at the Love Wall in his studio, London, 1961 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">The architect Oscar Niemeyer, Rio de Janeiro, 1951 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Retired potters at Wedgwood, 1952 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Ashley Havinden, of Crawford Advertising Agency, 1951 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda">

Coronation on Ice: Barbara Goalen makes her exit, St Moritz, 1953 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Barbara Goalen, Milling Around Lancashire, 1952 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Winston Churchill, Chartwell, Kent, 17 October 1954 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Winston Churchill, Chartwell, Kent, 17 October 1954 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Winston Churchill, Chartwell, Kent, 17 October 1954 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Rory and Alexander McEwen, Scotland, 1950 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Margot Fonteyn double exposure, hat fitting with Rose Vernier, 1949 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Critic Kenneth Tynan with his daughter, Tracey, Bayswater, 1953 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Antony Armstrong-Jones in his studio, 1952 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Henry Moore in his studio at Much Hadham, Hertfordshire, working on King and Queen, 195 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Pop artist Peter Blake with model Marie-Lise Gres at the Love Wall in his studio, London, 1961 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">The architect Oscar Niemeyer, Rio de Janeiro, 1951 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Retired potters at Wedgwood, 1952 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">Ashley Havinden, of Crawford Advertising Agency, 1951 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda">Coronation on Ice: Barbara Goalen makes her exit, St Moritz, 1953 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda ">

Coronation on Ice: Barbara Goalen in Coronation robes, St Moritz, 1953 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">

Coronation on Ice: Barbara Goalen in Coronation robes, St Moritz, 1953 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

"> Barbara Goalen, Milling Around Lancashire, 1952 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">

Barbara Goalen, Milling Around Lancashire, 1952 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

"> Winston Churchill, Chartwell, Kent, 17 October 1954 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">

Winston Churchill, Chartwell, Kent, 17 October 1954 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">

Winston Churchill, Chartwell, Kent, 17 October 1954 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda ">

Winston Churchill, Chartwell, Kent, 17 October 1954 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">

Winston Churchill, Chartwell, Kent, 17 October 1954 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

"> Rory and Alexander McEwen, Scotland, 1950 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">

Rory and Alexander McEwen, Scotland, 1950 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

"> Margot Fonteyn double exposure, hat fitting with Rose Vernier, 1949 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">

Margot Fonteyn double exposure, hat fitting with Rose Vernier, 1949 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">

Critic Kenneth Tynan with his daughter, Tracey, Bayswater, 1953 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda ">

Antony Armstrong-Jones in his studio, 1952 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">

Antony Armstrong-Jones in his studio, 1952 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

"> Henry Moore in his studio at Much Hadham, Hertfordshire, working on King and Queen, 195 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">

Henry Moore in his studio at Much Hadham, Hertfordshire, working on King and Queen, 195 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

"> Pop artist Peter Blake with model Marie-Lise Gres at the Love Wall in his studio, London, 1961 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">

Pop artist Peter Blake with model Marie-Lise Gres at the Love Wall in his studio, London, 1961 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">

The architect Oscar Niemeyer, Rio de Janeiro, 1951 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda ">

Retired potters at Wedgwood, 1952 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

">

Retired potters at Wedgwood, 1952 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda

"> Ashley Havinden, of Crawford Advertising Agency, 1951 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda">

Ashley Havinden, of Crawford Advertising Agency, 1951 - Photo: Elsbeth Juda">