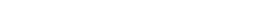

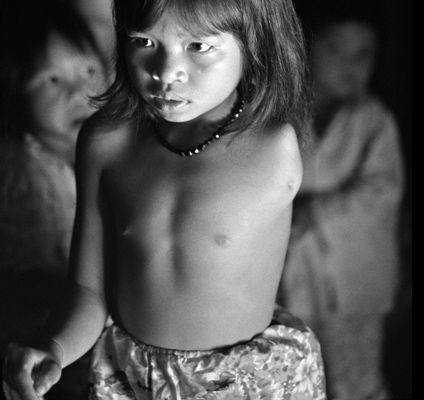

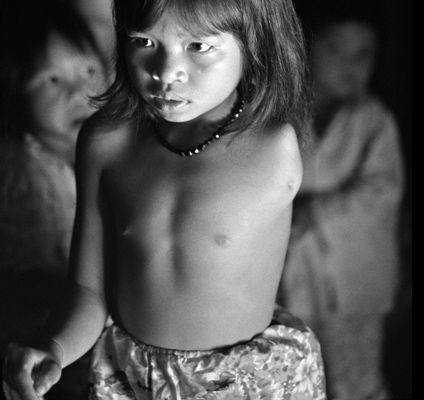

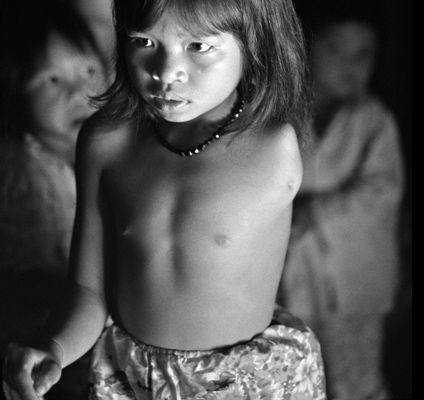

Quynh Lan, 11 years old, at her home in A Luoi. Her father was sprayed many times - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

">

1967 - US military over Viet Nam - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books "> Quynh Lan, 11 years old, at her home in A Luoi. Her father was sprayed many times - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

">

Quynh Lan, 11 years old, at her home in A Luoi. Her father was sprayed many times - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

"> Pham Thi Thuy Linh was born in Ho Chi Minh City with no arms and has learned to write using her feet. Her grandfather was an army officer in the former regime and worked on the aircraft that carried and dispersed Agent Orange during the war - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

">

Pham Thi Thuy Linh was born in Ho Chi Minh City with no arms and has learned to write using her feet. Her grandfather was an army officer in the former regime and worked on the aircraft that carried and dispersed Agent Orange during the war - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

"> Checking the tip of the branches for destructive insects: this is a new plantation in the heavily defoliated A Luoi Valley. The treeless denuded hills in the distance are covered with scrub - the American grass - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

">

Checking the tip of the branches for destructive insects: this is a new plantation in the heavily defoliated A Luoi Valley. The treeless denuded hills in the distance are covered with scrub - the American grass - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

"> Near the old American base south of Quang Tri, a young girl stands guard over her patch of saplings marked off by rows of old artillery shells. She is responsible for their safety, warding off birds and rats - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

">

Near the old American base south of Quang Tri, a young girl stands guard over her patch of saplings marked off by rows of old artillery shells. She is responsible for their safety, warding off birds and rats - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

"> Le Thi Hoa, 14, born with deformed fingers, proudly demonstrates her excellent penmanship - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

">

Le Thi Hoa, 14, born with deformed fingers, proudly demonstrates her excellent penmanship - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

"> Baby with no name brought from Vinh Long Province to Tu Tu hospital by her mother, Dang Thi Hong Khuyen. She was born in November, 1998 with hydro-encephalitis, and died a month after this photo was taken - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

">

Baby with no name brought from Vinh Long Province to Tu Tu hospital by her mother, Dang Thi Hong Khuyen. She was born in November, 1998 with hydro-encephalitis, and died a month after this photo was taken - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

"> Gigi Giannuzzi on press with 'Agent Orange', Trolley Books - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths

">

Gigi Giannuzzi on press with 'Agent Orange', Trolley Books - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths

"> Gigi Giannuzzi on press with 'Agent Orange', Trolley Books - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths

">

Gigi Giannuzzi on press with 'Agent Orange', Trolley Books - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths

"> Philip Jones Griffiths at his last public talk at the Frontline Club, London, 2007 - photo Rhodri Jones

">

Philip Jones Griffiths at his last public talk at the Frontline Club, London, 2007 - photo Rhodri Jones

">

1967 - US military over Viet Nam - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books ">

Quynh Lan, 11 years old, at her home in A Luoi. Her father was sprayed many times - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

">

Quynh Lan, 11 years old, at her home in A Luoi. Her father was sprayed many times - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

"> Pham Thi Thuy Linh was born in Ho Chi Minh City with no arms and has learned to write using her feet. Her grandfather was an army officer in the former regime and worked on the aircraft that carried and dispersed Agent Orange during the war - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

">

Pham Thi Thuy Linh was born in Ho Chi Minh City with no arms and has learned to write using her feet. Her grandfather was an army officer in the former regime and worked on the aircraft that carried and dispersed Agent Orange during the war - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

"> Checking the tip of the branches for destructive insects: this is a new plantation in the heavily defoliated A Luoi Valley. The treeless denuded hills in the distance are covered with scrub - the American grass - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

">

Checking the tip of the branches for destructive insects: this is a new plantation in the heavily defoliated A Luoi Valley. The treeless denuded hills in the distance are covered with scrub - the American grass - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

"> Near the old American base south of Quang Tri, a young girl stands guard over her patch of saplings marked off by rows of old artillery shells. She is responsible for their safety, warding off birds and rats - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

">

Near the old American base south of Quang Tri, a young girl stands guard over her patch of saplings marked off by rows of old artillery shells. She is responsible for their safety, warding off birds and rats - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

"> Le Thi Hoa, 14, born with deformed fingers, proudly demonstrates her excellent penmanship - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

">

Le Thi Hoa, 14, born with deformed fingers, proudly demonstrates her excellent penmanship - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

"> Baby with no name brought from Vinh Long Province to Tu Tu hospital by her mother, Dang Thi Hong Khuyen. She was born in November, 1998 with hydro-encephalitis, and died a month after this photo was taken - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

">

Baby with no name brought from Vinh Long Province to Tu Tu hospital by her mother, Dang Thi Hong Khuyen. She was born in November, 1998 with hydro-encephalitis, and died a month after this photo was taken - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths Foundation / Trolley Books

"> Gigi Giannuzzi on press with 'Agent Orange', Trolley Books - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths

">

Gigi Giannuzzi on press with 'Agent Orange', Trolley Books - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths

"> Gigi Giannuzzi on press with 'Agent Orange', Trolley Books - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths

">

Gigi Giannuzzi on press with 'Agent Orange', Trolley Books - photo: Philip Jones Griffiths

"> Philip Jones Griffiths at his last public talk at the Frontline Club, London, 2007 - photo Rhodri Jones

">

Philip Jones Griffiths at his last public talk at the Frontline Club, London, 2007 - photo Rhodri Jones

">