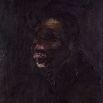

Undeniably gifted, world-over revered, obstinately private, early on, artist and designer Keith Cunningham made a pivotal choice that would change his life. While continuing to paint feverishly, continuously for decades, he decided never again to show the paintings in public. And never did he change his mind in his lifetime.

His canvases famously stacked up at the studio and some at home with their back to any passing visitor, nothing could make him budge and turn them around. On the contrary, rather than having his interest rewarded, an enquirer’s curiosity would be dealt with as a hostile intrusion, and sharply dealt with by way of deadly blow…

—

Having walked out of school and home at 15 to fend for himself, he landed himself a job in the art department at David Jones Department Store in Sydney. There me met the renowned graphic designer Gordon Andrews who was consultant to the store. On Andrews’ suggestion he studied in the evenings and eventually became his design assistant.Inspired by a meaningful gift in form of a book on the ‘Bauhaus’, Cunningham started to dream further afield. Having set his sight on Chicago to study under Moholy-Nagy, he was convinced by Gordon to go to London instead so that he could assist Gordon on the Festival of Britain in 1951.

Hence the stylish, creative and resourceful young Australian landed on British shores in 1950. Walking into Central School of Art - innocently and unannounced - he was instantly offered a place on the graphic design course (1950-52).

He was very busy day and night on all fronts. The Festival of Britain was a huge event in post war Britain giving rise to a new era to British creative arts. Cunningham being greatly involved on ever so many levels, was plunged right into the middle of the buzzing creative new London.

Bobby Hillson who herself would become known not only for her Vogue illustrations, but for creating the celebrated Fashion MA at St Martin’s:

I met Keith at the Royal College Xmas dance in 1950. Walking me home he asked me if I liked the posters,… I looked around and there were his posters — on every bus stop, everywhere, as he’d just won the London Transport Poster Competition. I am sure if I hadn’t liked them, things would have turned out differently…”

Evidently Bobby did say she liked them, as,... the rest is history, married 6 months on, only Keith’s death could, and finally would, part the pair.

On leaving the Central, he wanted to continue his studies, but in painting this time, and applied to the RCA. Going in for the interview he was sent across from the graphics to the fine art department, he was asked to show his paintings..... he had to return soon after to re-apply after having painted some. He was not only accepted but also received a study bursary.

Studying alongside Frank Auerbach and Leon Kossoff among others, he found his true calling here, and painted with a passion.Some six months into the course he had yet a new idea … he decided not to paint at the college but borrowed a friend‘s studio outside instead. “It wasn’t so well received… but much better for me: I’d go in and present the paintings when needed” he’d later tell me at one of Bobby’s famed dinner invitations.

Understood — he wasn’t at the college ‘for the party’. Instead he worked hard, and did it his way — prompting John Minton (1917 – 1957) to describe him as ‘one of the most gifted painters to have worked at the Royal College’.

By the time he left the RCA in 1956 he’d pocketed a ‘First’ as well as a travel bursary on which he did his personal ‘Grand Tour’ [to come face to face with the works of his true masters at the Prado and Louvre] — and a continuation scholarship on which he could get a painting studio in London.

This coincided with modern post WW II British painting as a collective body becoming noted on the international art scene for the very first time. The modernist ‘London Group’ [formed as anti establishment movement ‘by artists for artists’ in 1913 in order to escape the stranglehold of the Royal Academy] had become extremely prestigious with its ‘golden era’ lasting from 1951 to 1964.

London was for the first time able to create a British position between the continental European art movements and an emerging US market fuelled by a strong economy and European vanguard exiles.Cunningham took part at the Royal Academy’s Summer Exhibition and exhibited at the Beaux Arts Gallery – then one of the most influential galleries in London.

Showing twice with the ‘London Group’, where his work was singled out by The Times art critic for its ‘power and suggestive presence’. Cunningham enjoyed rising fame and the support of London’s most influential collector couple of the time, Elsbeth and Hans Juda (publishers of The Ambassador). His paintings sold as far afield as Olinda Museum in Brazil, the North West Trust Collection in Northern Ireland.

After two years of showing Cunningham’s work the London Group asked Cunningham to become a full member of the group. To everyone’s surprise he declined. He started to withdraw instead. From 1967 he refused any other exhibitions offered – and never publically exhibited his work again.

Whether he was not prepared to succumb to artworld politics - or whatever else made him sway this way we will never know. But while continuing to draw and paint constantly, he did decide to close his studio to the eyes of the world, and rather earned his ways with graphic design where he continued to be a major player. Apart from exhibition design and magazine editorials, his longstanding collaboration with the late publisher Peter Owen OBE let him create the company’s most memorable hard back book covers, authors including Anais Nin, Hermann Hesse and Marquis de Sade.

In 2004, The Barbican reconfirmed his position in the forefront of British Design by including his work in the exhibition Communicate: British Independent Graphic Design since the Sixties. The Emergence of British Graphic Design. His graphic archives are now at Brighton University.

All the while he was lecturing part time at the London College of Printing – which led him to be mentor and teacher to a whole generation of graphic artists – the two days a week teaching left 4 days a week for painting.

- The paintings though, his life’s personal work, stubbornly remained, facing the wall until the day he died. In 40 years of working, there were about 17 studio visits of those who’d passed the test.

I am very glad I became one of the few in 1999. In retrospect it makes me smile that the coincidence of heading to the opera straight after added a little unexpected spark to the occasion by way of Vivienne Westwood platform heels and full length stretch velvet black and gold. A little touch not lost on Keith. Bringing along Tot Taylor who was to open Riflemaker a few years later, retro-actively means that one London gallerist actually had been shown the paintings in the studio.

There was work on every shelf, in every nook, cranny and drawer, all neatly organized and maximizing the space available; there were watercolours, ink drawings any size, sketches, and painting over painting,… the great oil canvases from the 50s stole the show.

Thanks to Bobby Hillson – the one and only continuous supporter from beginning to end – at last, now in 2016, they are here for the world to see.

Uscha Pohl

—

Keith Cunningham passed away on December 4, 2014, at the age of 85.

Keith Cunningham: Unseen Paintings 1954-1960,

30 September - 13 October 2016, Hoxton Gallery, 59 Old Street London EC1V 9HX

Private Keith Cunningham

Uscha PohlTags: