IN AND OUT OF AFRICA

Nigeria, March 1961

Living in their ancestral home in the north of Ibadan, Felicia and Gabriel Omoniyi had four young children and were expecting their fifth. Felicia Adedun was at forty years of age the breadwinner as cloth trader and Gabriel a poor farmer. In early ’61 the cloth trade decreased in area and their modest existence became impossible. For Felicia to find work elsewhere, the couple decided to pack up their children and travel south.

The pair had just found a temporary stay for their family in a village south of Ibadan, when Felicia unexpectedly went into labour two months early. Hurriedly Felicia and Gabriel began walking, trying to reach the nearest mission hospital on foot. However, the course of the birth had already set in. They had to stop in the bush – and on the ground by the side of the road Felicia gave birth to a little boy. When they thought the birth was over, to their surprise, a second, bigger child, appeared, a girl. Tragically the bleeding that followed became so intense that Felicia haemorraged and didn’t survive the birth of her twins.By the side of the road, in unfamiliar territory far away from home, Gabriel found himself a widowed father of six, without his wife to rely on to feed the family, with two premature newborns on his hands. Temporarily leaving his deceased wife, he managed to procure a bowl in which to place the two tiny infants and carried on the journey to the missionary station run by Irish Catholic nuns. Upon arrival Gabriel told the nuns the story and then readily departed, leaving the newborns with umbilical cords still loose and dangling. He’d given no name, only an address which later turned out to be false.

The mission station doubled up as orphanage and was desperately overrun with children in need. The nuns baptized the twins Thomas and Margaret. Weighing two and three pounds respectively they had close to no chance to survive. Within weeks they contracted malaria and every other imaginable disease. The likelihood of their survival decreased daily.

Hampstead, London, 18 April 1960

Richard Taylor, a 26 year old camera man for the BBC and his nineteen year young wife Allegra celebrated the arrival their first son, Benedict. Shortly after, Richard accepted a three year contract to set up the first television station in Ibadan, Nigeria. The young Taylors were excited to start a new life in Africa and set out for the great adventure.

Ibadan, Nigeria, 18 June 1960

Richard went about setting up the station, while Allegra settled into life as an expat wife. Yet after a year of endless teas and lunches discussing the failings of everyone’s household help, Allegra felt stifled by her purely social existence while her husband was away at work.Frustrated, Allegra started looking beyond the immediate circle of acquaintances and befriended an Irish nurse who was the head of the local mission hospital. Through her she learned about the despairing conditions at the orphanage.

One day in early June ‘61 Allegra decided to take the leap and went to the mission station to see if she could help out. Upon arrival however, rather than welcoming her in to help, the nurses promptly handed her the two most fragile children:

10 week old sickly twins struck with malaria. Could she take these two home to nurse them? She did.

When Richard returned from work that day, he had the surprise of his life. But together Richard and Allegra took on the challenge to rescue the two little children.

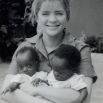

Calling them Tim and Femi, they went to work with determination: at three months, the twins were still desperately under weight, only six to seven pounds each. Allegra brought in their Maltese family doctor to take charge. The doctor would come to the house every day to tend to the rashes and boils on the twins’ skins.

They were so sick they were only able to take in a teaspoon of milk at a time, and had to be fed - rather continuously - with a miniature doll’s bottle. The twins’ experience in the first few weeks at the orphanage was unknown. But each time they were picked up their tiny bodies would turn into planks of wood. They cried constantly, riddled with fear. The feedings had to be every half hour around the clock.Tim showed his very first smile after fourteen long weeks; Femi followed suit not long after. Both started to giggle and smile rather than tightening up when touched. Trust had been established and they were finally able to respond to a person without anguish.

A year later, Richard had completed his work in Ibadan and the family was set to move on to Port Harcourt in the South East. Before leaving town, Richard and Allegra went back to the Oluyoro Mission Hospital to see if the father of the twins had returned to claim the children.

There had been no sign of the father, so the couple went to find him at the address he had given. But they found that no one in the village even knew of him, the family or the story of the twins whose mother had died in childbirth. The mission station did not express any interest in taking the children back, so Richard and Allegra decided to embrace them as part of their family.

When time came for the Taylors to return England in 1963, Richard and Allegra decided to adopt the twins through the British courts. It took one hour in court and they had become British citizens – Timothy Joe Taylor and Olufemi Claire Taylor.

England, 1963

Young Femi’s passion and natural ability was in dance. First introduced to the art form by Allegra’s sister who was an accomplished dancer and teacher, Femi took dance classes from the age of four. At sixteen she was awarded a grant for the prestigious dance school ‘The London School of Contemporary Dance’ and started the day after her O Levels.Tim excelled in boxing, and at eighteen became Britain’s lightweight champion. But while he left the sport behind to become a fine jeweller, Femi pursued a career as professional dancer within the first year at dance school.

Femi remembers: “It was a three year course, but in the last term of the first year, I saw an audition advertised in The Stage for a new major West End show coming up. It was an all Black American cast and they were looking for a British dancer to complement the team and cover three or four parts in the show.

Auditioning outside the school was strictly forbidden but I couldn’t resist. After the first audition, two out of twenty were called back, myself and another girl. A grueling 2 hour-audition later, I was offered the part in the award winning “Bubbling Brown Sugar“. This meant my immediate exit from the school - and was the ticket to life as a professional dancer at seventeen.

I stayed the entire two year run of the show with the original American cast. Some of them had attended the New York based Alvin Ailey School for Dance I had long dreamt of attending. Now my income from the show and the paycheck of my first film in Berlin, Menahem Golan’s The Apple (1979), allowed me to go.”

Femi started the Alvin Ailey School for Dance in the summer of 1979, but in 1980 followed a call to return to Britain and take part in The Wiz, at the Sheffield Crucible Theatre, directed by Peter James. Soon after things started happening back in London.“In 1981 Andrew Lloyd Webber was getting ready to launch Cats, and my agent asked me to prepare a piece of poetry for the audition. The concept of Cats was a complete novelty - an all dance show without an actual plot of action - directly based on T.S. Elliot’s Old Possum’s book of Practical Cats. To start with, no one had particular confidence in the show and securing backing was difficult. To get it off the ground, the show was in parts financed by the cast itself.“

“The turning point only came when Judi Dench in the lead role snapped her achilles tendon in rehearsals. To this day I can still see her collapsing between us and screaming in pain. After the accident, unable to find a fitting actress for the lead role, the company cast a singer instead - Elaine Paige. For her as Grizabella, the director Trevor Nunn constructed the lead song by collating parts from different TS Elliot poems. It was called ‘Memories’, and the rest is history.“

Femi stayed with the original cast until ‘82 as Tantomile, under-studying Bombalurina, when in the middle of it she was called to audition for a film.

“The director had insisted I needed to bring my swimwear, and I really wasn’t sure if I should go. I did go after all, and as result of the second dance audition I was cast as the Twilek dancer Oola in Return of the Jedi. I rehearsed for Star Wars during the day while performing Cats in the evenings and for the actual shoot at Elstree studios I took a week’s leave from the show. Richard Marquand was the director.”

When her first Cats contract came to an end, Cameron Mackintosh’s office asked her to continue on as Bombalurina. “I declined, as I didn’t feel ready to take on the responsibility of a lead role with eight shows a week. When they re-offered in 1984, I took it on.“RETURN TO NIGERIA

In 1982 Femi’s adoptive father Richard returned to Nigeria to make a documentary about the traveling theatre Ogunde. But he also had a personal mission: to finally track down the twins’ family.Richard had a close friend in Nigeria who offered help visiting villages neighbouring the missionary station by Ibadan to do some detective work. He asked all the chiefs in the area if they remembered the mother of the twins back who died in childbirth in 1961.

Simultaneously Richard ran announcements on the local radio station and newspapers, offering a reward for whoever could lead them to the twins’ family. Richard was warned to be careful, as anyone could try and rake in the reward with bogus leads. However, the miracle they had hoped for did happen.

The twins’ eldest brother Sunday heard the radio announcement, and was in fact the only person who came to the station. An appointment was arranged for Sunday to meet Richard, who knew immediately that he was one of the biological siblings because of the strong resemblance to his adopted children. Through Sunday they traced Gabriel, another sister, and two other brothers.

The news were unbelievable for Tim and Femi back home in London. Throughout the following year, tape recorded messages and gifts were exchanged while the siblings planned a trip to visit.The BBC were keen to make a film of the twins’ return but for some reason did not want Allegra to be part of the film or trip. Femi says: “This seemed utterly pointless and bizarre, after all she had first found us and taken us with her to save our lives.” Allegra refused to cooperate without her participation with the effect that the BBC dropped the project. It turned out to be a blessing: already the Nigerian press was plenty to handle for the returning twins.

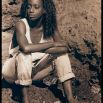

Femi: “Going ‘back’ to Nigeria was a significant moment – Tim and I went to find the missing jigsaw piece in our lives. Staying with our senior sister instead of a hotel allowed us to bond and to see how true Yoruba Nigerians lived and survived on a day-to-day basis. Two buckets of water for daily washing, chicken in and out of the house, pounding yam in the yard, cooking on a single burner for two and a half families, which means about 15 people. Travelling miles in a car stuffed with chicken boxes and anything else on the planet, in unforgiving heat.“

Everyone in the area was extremely hospitable and welcoming, excited for the twins to be ‘back’. People would put money in their hands when passing them in town, leave food gifts on the stoop of the house where they were staying. Gabriel was ever so proud and decorated his room with a cutting the front cover of Drum, the leading magazine for West Africa, featuring Femi.

On the other side of the coin, there was pressure. “They kept saying ‘you need to stay, why don’t you marry Nigerians, why doesn’t Allegra leave you here with the family.’ My elder sister was determined to cut my hair and swap my clothes for African tunics. It made our stay rather difficult. We were Westerners. We neither remembered our early life in Africa, nor felt that Nigeria was our home, irrespective it being our birth place.Being there was shocking to us in many ways. It was hard to understand that the richest country in Africa with all its oil resources could be so ruined by corruption. Instead of being invested in the country and shared with the people into the country, the wealth ends up as personal investments in property in Knightsbridge and Hyde Park, leaving Nigeria on its knees.” [continue the article: FEMI TAYLOR - PART 2]

Femi Taylor — Part 1

Uscha PohlTags: